Blog/2024-11-14/GM Plants

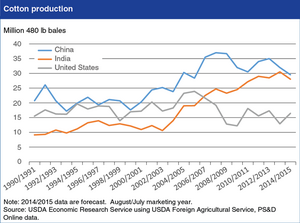

One of the things that amazed me when I moved to America is the anti-GMO movement here. I was born in 1988 so I was about 14 years old when Bt Cotton was introduced to India. About this time I was obsessed with reading the news (I'd finish the newspaper every day in the morning) and the back page of one of the supplements to The Hindu was the Science and Technology section. For years, it would talk about how this new genetically-modified cotton was going to change everything. And it did! India's cotton production soared. This was a massive success. So of course India leaned into GMOs, right?

Well, apparently not. Since GMOs were only really starting to become popular, and opposition wasn't really that widespread, cotton managed to sneak under the radar. Afterwards, brinjals (US: eggplants) weren't allowed to be grown. So, in reality, what happened is that I left India with this belief of the enthusiasm around GMOs because of cotton's success but I left before the opposition to GMOs solidified.

So what happened is that while GMO opposition increased worldwide, I attributed it to the US being anti-GMO and my home country not being so. It turns out, in fact, that this was completely erroneous.

In India (and worldwide really), we use genetics as a scanner tool rather than an editing tool. The process of Marker-assisted selection is quite similar to what Julie and I did for our embryos. You use genetics to look for certain subsequences in the DNA associated with something like drought tolerance and then use natural variation to produce plants of that variety. Then you repeat that process until you have a suitable plant. One big difference is that you're not really going to get a fancy thing like Bt cotton out of it since those gene strings from Bacillus thuringiensis are not exactly going to spontaneously develop on the timescales we're working with here.

What we did for our embryos is very precise, in comparison, but fundamentally the same concept in that it's a scan rather than a write. We looked for the state of a specific gene in the DNA sequence. But still, it's funny to come all the way around to this.